Why Do Lebanese People Love Clichés About Lebanon? Let’s Talk About It

Lebanese people disagree on a lot of things, and that includes their own history. But what are things we ALL have in common? We’re obsessed with Fairuz, hummus, and dabke. And there’s actually a reason Lebanese people love these clichés about Lebanon.

An article by Sune Haugbolle, an Associate Professor in Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Copenhagen, titled “Public and Private Memory of the Lebanese Civil War,” sheds some light on this topic . Let’s break down the major points so that you don’t have to read the 10-page (ish) publication.

PS. this is an extremely simplified overview. Everything relating to memories of the Lebanese Civil War could be better explained by scholarly publications and media experts, some of which are linked in this blog.

Why is there no unified history of the war?

Instead of going in circles about what happened between 1975 and 1990, a major parliamentary decision was made to ‘officially’ end (up for debate) the civil war in Lebanon.

In 1991, the parliament passed a general amnesty law that applies to crimes committed before March 1991 in order to “wipe the slate clean and for the leaders to remain in their seats”. Haugbolle refers to this as the magical formula of la ghalib la maghlub, which translates to no victor, no vanquished.

Image source: Instagram.

This basically means that all the crimes (and there were a lot of them) that took place before that date were excused, absolving our oh-so-great leaders from any legal consequences.

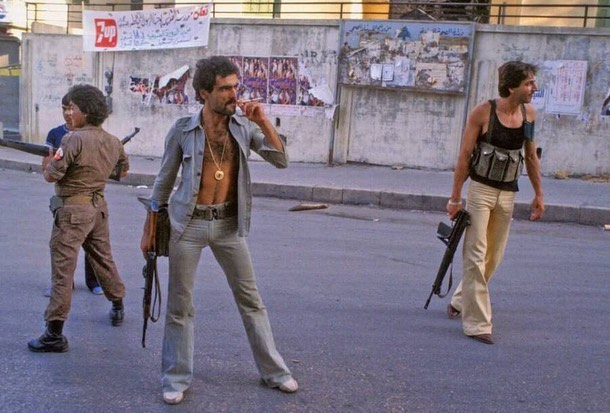

Anyway, what matters is what happened AFTER this law was passed. What about all the families who lost their loved ones? What about the people who disappeared during the conflict have, to this day, not been found? The Lebanese people needed closure, but the militia heads who committed atrocities were reintegrated into the state apparatus. How could they get closure when even the state was acting like everything that took place during that traumatizing period didn’t happen?

Image source: Instagram.

State amnesia in Lebanon

What the Lebanese government was doing at the time was completely ignoring past conflicts in their period of post-conflict resolution.

And what made things worse was a law regulating broadcasting was enacted in 1994 that prevented inciting/provoking any sectarian or religious chauvinism. Instead of having one national television and radio station (which was true before the civil war), Lebanon’s broadcasting community had 52 TV stations and 120+ radio stations belonging to different militias. It was near impossible to protest all these different broadcasting stations, regardless of what propaganda they were spewing, because of that law that was enacted in 1994. People were furious. No one could be held accountable, and no collective responsibility could be taken by Lebanese society for partaking in the crimes committed.

Image source: Instagram.

So what did the Lebanese government start doing? They united people over clichés.

Fairuz, hummus, and dabke: Lebanon’s post-conflict resolution

Unlike most countries, there was no official memorial or monument of the civil war. That would hinder all the government’s efforts at silencing the masses, right? Even if there was some kind of institutionalized memory of the war, it’s not like there were any state efforts to have a unified history about the war.

There have been attempts to unify Lebanese history back in the late 90s-early 2000s by scholars, historians, and experts, none of which were very effective. You can read more about those in this article by Elsa Abou Assi.

Picture: Unofficial monument commemorating the end of the Lebanese Civil War in Yarze, Lebanon. By French-American artist Armand Fernandez.

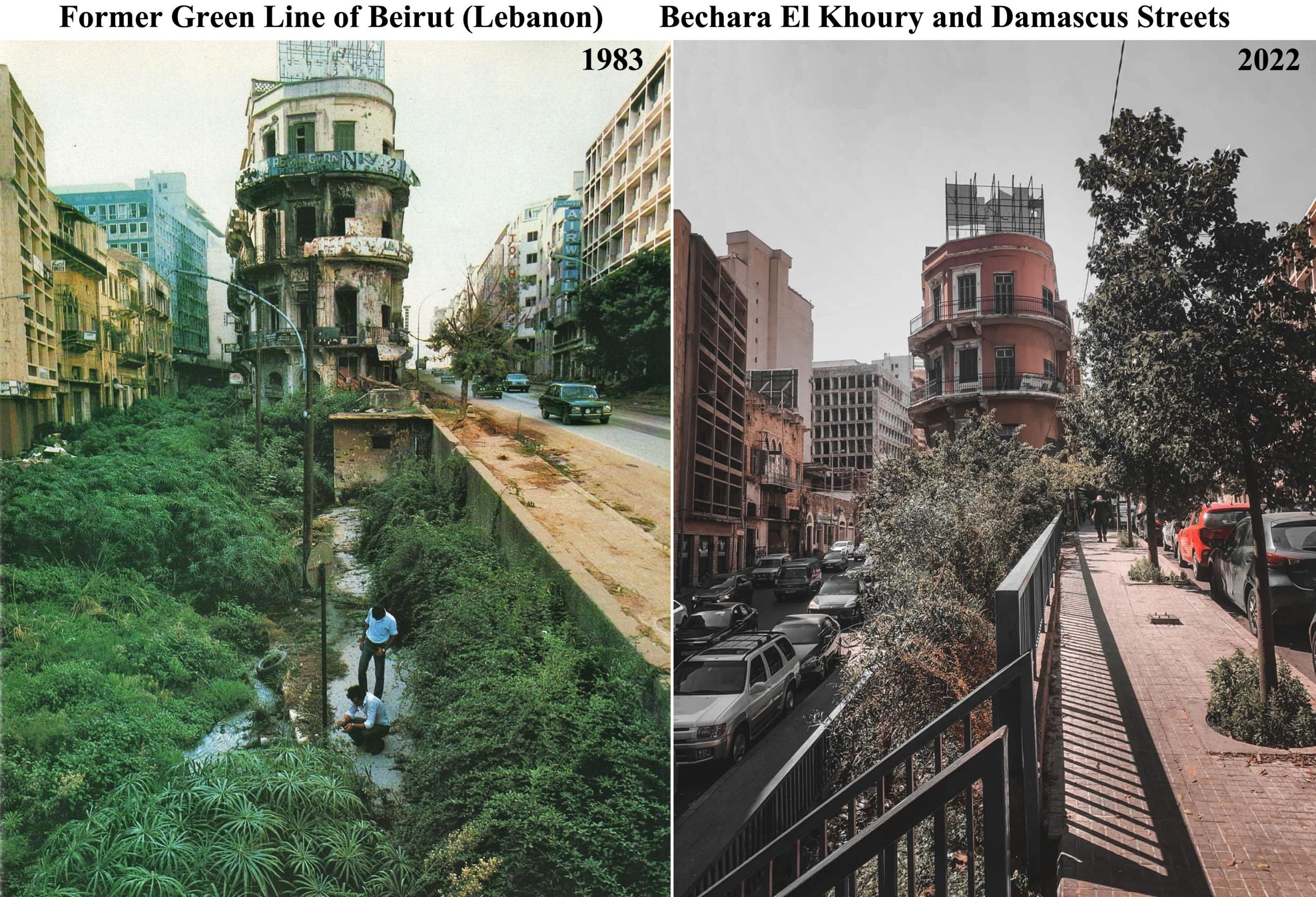

So as Downtown Beirut was completely demolished and rebuilt (allegedly to erase all evidence of what once was), the revived image of Lebanon was promoted to be a “commercialized, nostalgic, and utterly depoliticized version of Lebanon’s past”.

And what’s more commercial, nostalgic, and depoliticized than Fairuz? Even today, she stands as a symbol of Lebanon. Now throw in hummus because the foreigners adore it, and dabke because it’s just so fun at Lebanese weddings. Fun enough to make you want to dabke your differences away.

This is the image of Lebanon that the government was promoting. It’s no coincidence that these aspects of our culture are always being promoted to the public. Most, if not all, of us are obsessed with these three things. They’re some of the proudest aspects of our culture.

Image source: Reddit. The Green Line, 1983 vs. 2022.

Lebanese nostalgia or trauma?

We all feel a certain nostalgia for Beirut’s “golden age,” even though most of us haven’t experienced it firsthand. This sentiment is likely influenced by the depoliticized image of Lebanon that the government promotes.

While we may adopt these clichés as part of our Lebanese identity, it’s undeniable that the trauma, including the generational trauma passed down from our parents, is very much alive and well. This doesn’t mean you should stop loving these clichés because they do represent a part of our identity. It is interesting to consider, however, that this collective obsession exists for a reason.

If you still want to read the Haugbolle article, you can click here.

Do you agree that Lebanese people love these clichés about Lebanon? You might also be interested in West Beirut Cast: Then Vs. Now.