The Hakawati: A Look Back At One Of Beirut’s Finest Characters

Who was the hakawati and what was their role in society? Uncover the stories behind this magnificent character which shaped the cultural scene in Beirut for decades, all on a new episode of Beirut’s Collective Memory narrated by the talented Tarek Kawa.

Can you imagine living in a world without visual storytelling? We now call that ‘television,’ or ‘TV’ for short. This was the case in Beirut in the nineteenth century, and generally, all the Arab cities. They all had a problem with entertainment, especially at night. Where were they supposed to go?

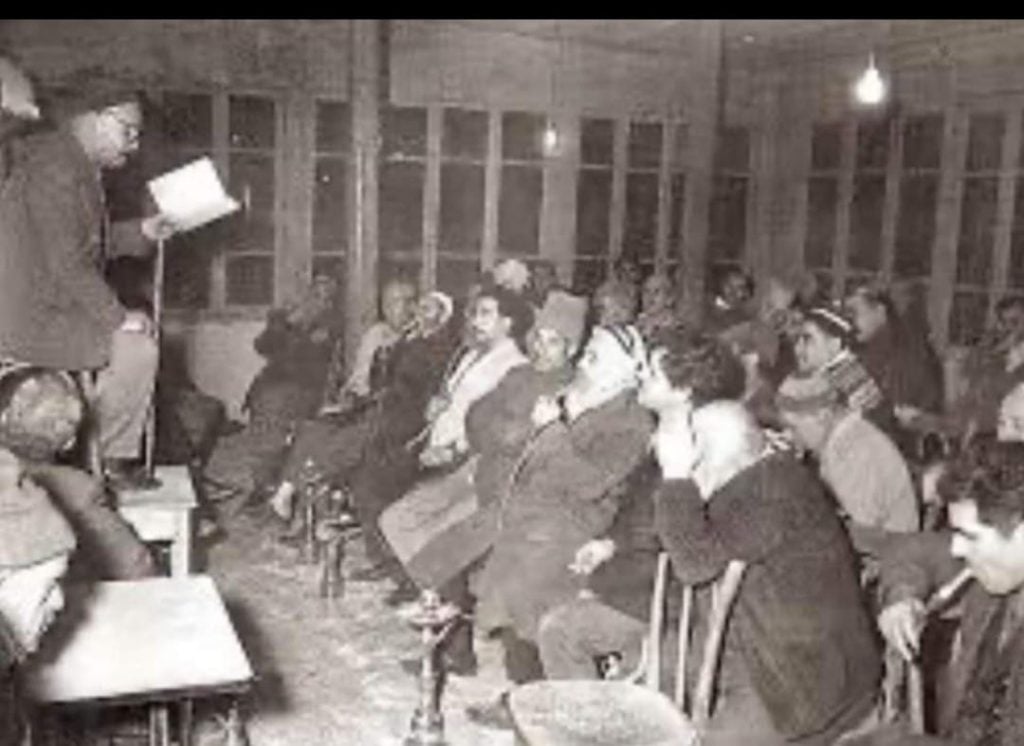

There was nothing but the coffeeshop (ahwe). Sometimes there would be familial visits where they would talk to each other, but a visit to the cafe was a means of entertainment and at the same time, it was very important for the community. Especially for the children who were growing up in Beirut at that time. They were listening to stories and tales and thus they were absorbing the culture of that time. And they were learning the customs and traditions of the city they were living in. Who was conveying this culture to them? The coffeeshop. And inside the coffeeshop, Hakawatis (storytellers). Yes indeed. His name became The Hakawati.

We often hear the word storyteller (Hakawati) these days, and we smile because for us, it is associated with a comical figure found in coffeeshops. Our parents and grandparents used to tell us about it, but in reality, the Hakawati was a very important role back then. First off, there were two types of storytellers: There was the storyteller who always held a book, carrying it everywhere throughout the day.

He takes the book, sits on the stage, and reads from it. Then there was the other type: the one who has memorized everything and knows many verses, his educational and cultural level is significantly higher than that of the first. He could stand on stage. He would act out the story. He would hold onto his cane when he told about Antar striking with his sword, he would strike with his cane. He would hit the ground with his cane whenever a sound effect was needed.

This was the difference; the storyteller had the ability to address people, to attract the hearts and minds of these young children at that time, and this was very important. The difference between the two types of storytellers was also apparent in their compensation. Meaning, the storyteller who read from a book normally used to get paid four bars per night. The storyteller who was educated and knew everything by heart would stop and collect a bar from each table, for each tale.

The clever storyteller was able to empathize with the character, interact with people, change his voice when speaking the hero’s lines, he could act… he had the ability to captivate the audience, and thus he was able to stop the story during the hero’s crucial moments…and here began problems with hakawatis. I mean, once when a hakawati was telling about Antar that they found Antar and tied him with chains and tied him to a tree…the abadayat at the coffee shop insisted this was “invalid” and wouldn’t let the storyteller go home unless he reverses the situation, completes the story and breaks all the chains of Antar. And the whole point is that there must be bravery, gallantry, and chivalry in every story, and the oppressed must always win.

Do you have stories or anecdotes to share about Old Beirut? Email us!

collective-memory@beirut.com

To join the WhatsApp group that started it all and to tune in to more beautiful Beirut stories, click here

Join Group on WhatsApp

Sharing these stories would not have been possible without the work of following historians and researchers. If not for them and many others, Beirut’s heritage and history would have been lost. A special thanks goes out to:

Louis Cheikho – Taha Al Wali – Nina Jedejian – Hassan Hallak – Suheil Mneimneh – Abdul Lateef Fakhoury – Ziad Itani – Beirut Heritage Society – Ya Beyrouth Page