Lebanese “Service” In The Old Days: Oum Kalthoum And 25 Piastre

What was taking the “service” (shared taxi/van) like in the old days? Take a walk down memory lane with us. Hit the play button on the below recording and read along!

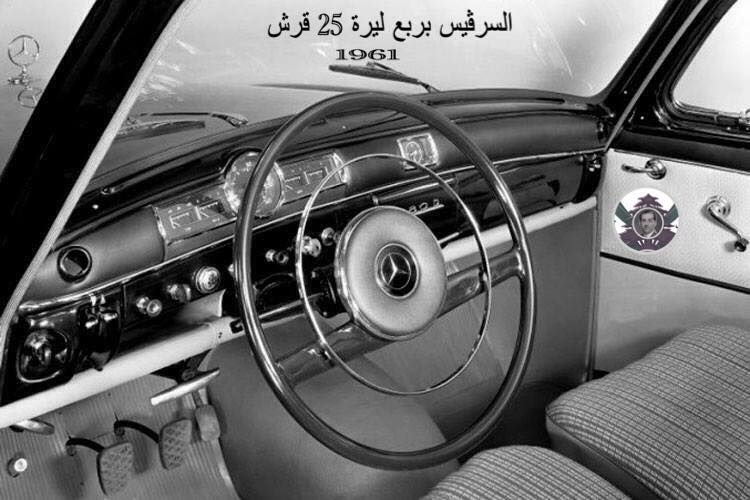

“Your manners are calling and so is your gentleness, so please calmly close the car door.” This is one of the many sayings you’ll see plastered on a Mercedes 180 service. And what does the driver of this car look like? For one, his hand will be resting on the steering wheel with his right finger raised and gesturing for you to get in, all while his elbow is pressed against the horn. His left hand would also be hanging out the window.

The interesting part of the service driver picking up passengers is that half of his customers are the same people because he works the same routes. As a result he knows every passenger, knows right away if they are a customer or not, as well as their name, where they live, and (on their way back) exactly where they get off.

The service was important at that time, and despite the fact that many people had cars, where would you park your car when you went Downtown or to commercial markets? Therefore, most people preferred to use the service.

Many people used to walk Downtown knowing that they would use the service on their way back home. But have you ever wondered how all service cars came to be Mercedes 180 and 190 models? The distributors of Mercedes (both back then and now), Gargour lowered the prices of these vehicles and offered very comfortable installment plans that allowed everyone with a red license plate, or anyone wanting to invest in a red plate, to buy a Mercedes 180 or 190. Meanwhile, the slightly elevated taxi cabs used the models of Mercedes 200 and 280 from Gargour.

And indeed, these were very durable cars, light on expenses, and can accommodate five passengers… but God help the person sitting in the middle upfront. Mercedes also helped by having the gearbox on the steering column so there were no gearsticks on the ground which would result in the loss of passenger space.

When you got in one of these Mercedes 180 services, if you sat in the back, you could hold on to a a chrome handle on the back of the front seat. But if you sat in the backseat, you would be missing out on a lot. First of all, you wouldn’t see the pictures on the dashboard, nor will you see the money placed on the speedometer: halves, quarters, dimes, francs in the cigarette ashtray that contained coins. The sun shade for the rolled liras, and of course the driver’s photo when he was young and his kids if they’re married, and most of the time a blue evil eye bead hanging from the mirror.

A few had a rotating fan mounted on the dashboard, and then you have the yellow towel: either on the driver’s lap, or he put it under his hand that is hanging from the window if the sun is strong… or tied to the signal lever. On the dashboard was also a plate with his name, the town he comes from, and the license number of the car he is driving… and of course instructions for you to close the door gently.

Then came the radio, of course you would listen to his music, with the majority of us having memorized Umm Kulthum’s songs from these service rides. And having the radio on is always miles better than him starting a conversation about politics. And if he didn’t like what you were saying, he would turn the radio back on and blast it. The speed of the service was directly dependent on how many passengers are in it: if he’s driving calmly, it means he’s missing a passenger or two …and if he’s driving fast, it means he’s at full capacity and wants to unload quickly. The fare was a quarter Lira, but there are those lucky people who live on downhill slopes towards the city, the driver would put it in neutral… and take only 15 cents from you.

Those were the days.

Do you have stories or anecdotes to share about Old Beirut? Email us!

collective-memory@beirut.com

To join the WhatsApp group that started it all and to tune in to more beautiful Beirut stories, click here

Join Group on WhatsApp

Sharing these stories would not have been possible without the work of following historians and researchers. If not for them and many others, Beirut’s heritage and history would have been lost. A special thanks goes out to:

Louis Cheikho – Taha Al Wali – Nina Jedejian – Hassan Hallak – Suheil Mneimneh – Abdul Lateef Fakhoury – Ziad Itani – Beirut Heritage Society – Ya Beyrouth Page