Toot Toot 3a Beirut: The Tramways Of Beirut

The Beirut tramway, nicknamed “Abu al-Fakir” (the poor man’s father), began its unique journey in the twentieth century. We will talk about the evolution of this mode of transportation, which was one of the major electric public transportation methods not only in Lebanon, but across the Middle East.

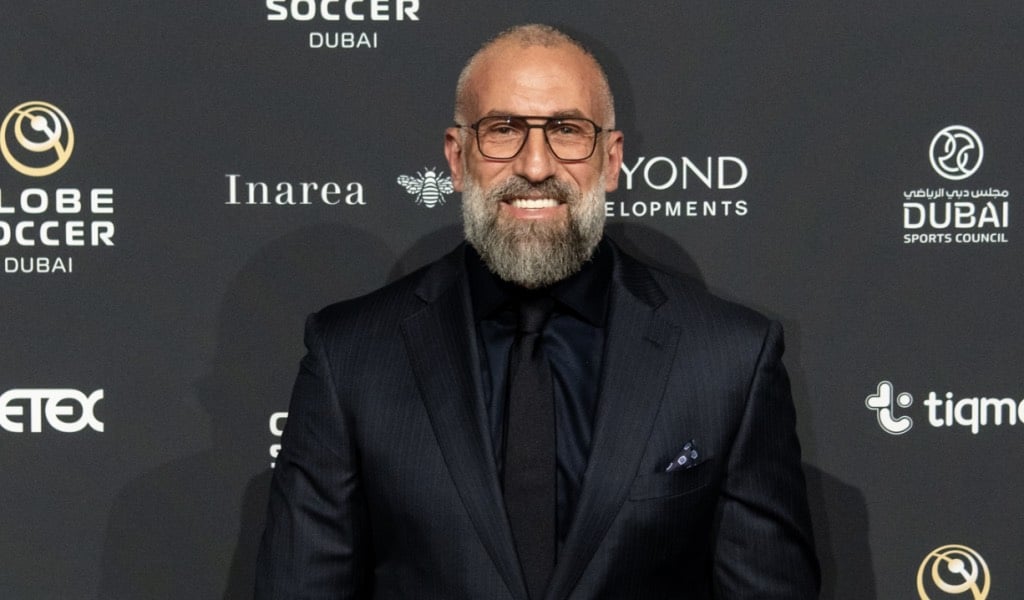

Discover the details of Beirut’s tramway and its impact on the lives of the residents of Beirut and their city in a new episode of Beirut’s Collective Memory with our unmatched narrator, Tarek Kawa!

The early tram system of the Beirut tramway was a tram car, but it was pulled by mules and donkeys before the carts became electric.

A Belgian company that arrived in Beirut at the time was given authorization to handle the project of improving the tram system, so long as the state continuously supplied it with electricity and lighting to the streets of Beirut.

The railroads expanded their network all throughout Beirut in 1908, connecting it to Furn El Chebbak, which was the border between Beirut and Mount Lebanon. This made it an essential mode of transportation between the two provinces.

The main stations played a crucial role in the transport of goods and urban development in the area based on the tramway network. These stations were the Port and the Mar Mikhael area. Over time, many institutions such as schools, hospitals, universities, theaters, cafes, market, and government agencies established themselves near the tramline for ease of transportation.

Over the years, the number of tram cars went from 13 to 52 in 1912, then increased to 112 in 1928 after the mandate, finally reaching 212 in 1934 after a French company claimed ownership of it.

Of course, people’s attitudes towards the tram were different when it first appeared compared to 1934. Initially, the locals were afraid of it, referring to it as the “devil’s wheel” or the “moving neighborhood”. During that time, it had two forms: a larger enclosed carriage that could carry 50 passengers and a smaller version for 30 passengers, divided into two sections – one for women and one for men.

Stations were often named after one of two things, either after someone the company knows or has worked for, or after a household name. One of the first stations was named Al-Noueiri station after Abdelkader El-Noueiri, who was one of the first people to work on the tramway project. Another station was named Graham station, located near the American University of Beirut. It was named after Dr. Graham, a lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine who also had a clinic in the area, and by the way Dr. Graham gave the tramway drivers one majidiyyeh (Ottoman currency) a day to announce his name aloud every time they reached the station.

The ticket prices following the mandate were around 1-1.5 piastres before they witnessed an increase to 5 pilasters for second class, which consisted of wooden seating, and 10 piastres for first class, which was more comfortable woven straw seats.

The last option was the third rank where the people stood or hung at the back of the tram for free. Students had their own special cheaper pass, politicians and VIPs used to get free passes.

One of the strange things during the mandate is that the French state appointed a doctor for every tramway carriage to ensure that people do not have contagious diseases. Unfortunately in May 1964, the Lebanese government issued a decision to cancel the Beirut tramway.

Join us in a new episode to learn more and more about the hidden stories of Beirut.

عندكن قصص أو أي تعليقات حابين تشاركونا اياها؟ بعتولنا بريد إلكتروني

collective-memory@beirut.com

To join the WhatsApp group that started it all and to tune in to more beautiful Beirut stories, click here

Join Group on WhatsApp

Sharing these stories would not have been possible without the work of following historians and researchers. If not for them and many others, Beirut’s heritage and history would have been lost. A special thanks goes out to:

Louis Cheikho – Taha Al Wali – Nina Jedejian – Hassan Hallak – Suheil Mneimneh – Abdul Lateef Fakhoury – Ziad Itani – Beirut Heritage Society – Ya Beyrouth Page