Souk El Tawileh: Unveiling The Jewel Of Beirut’s Past

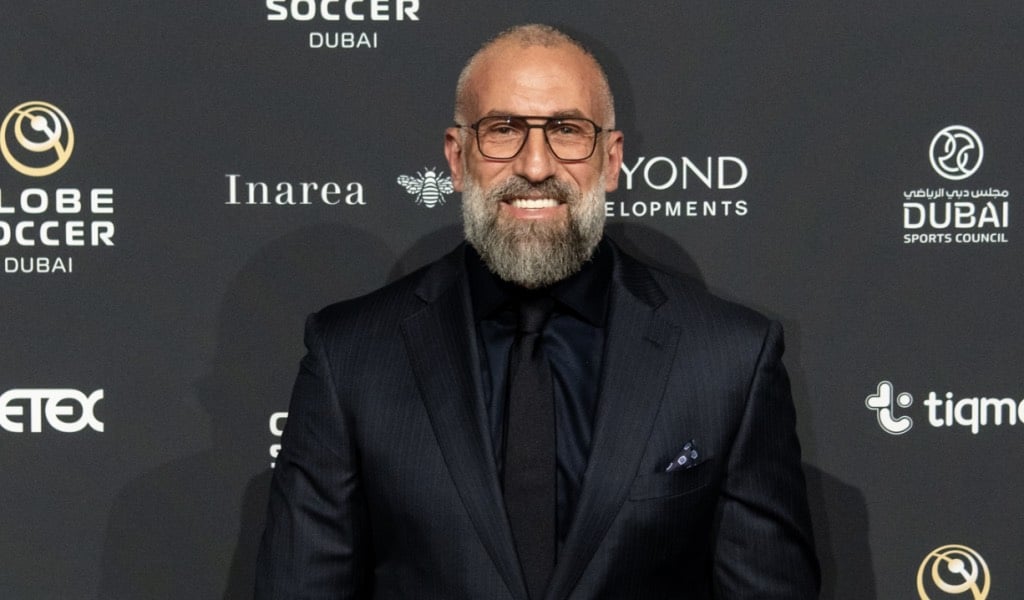

Today, we will get to know one of the most prominent historical markets in Beirut, “Souk el Tawileh”. The name has its unique origins and stories, and we will explore the history of this market and how it became a major center for trade and handicrafts in Beirut. Get to know some of the prominent figures and famous shops that were part of this market in a new episode of Beirut’s Collective Memory with Tarek Kawa.

You can’t complete the episodes about markets without mentioning Al-Tawileh market, how did it get its name? Let’s start with the stories.

The first story was that there were people from “Beit Tawileh” who had many properties in the market. The second story says that there was a tall Austrian woman who was a well-known and sought out tailor in the market, so they named it Souk el Tawileh. But the closest and most correct theory comes from its name in the old times: Darb el Tawileh (the Long Path).

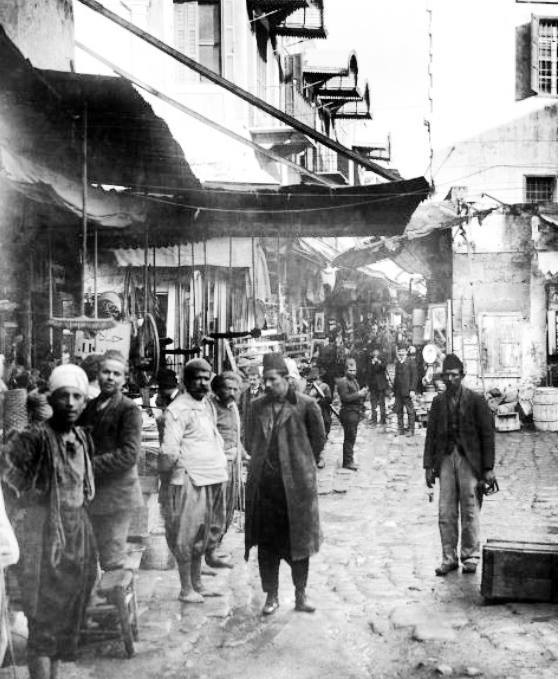

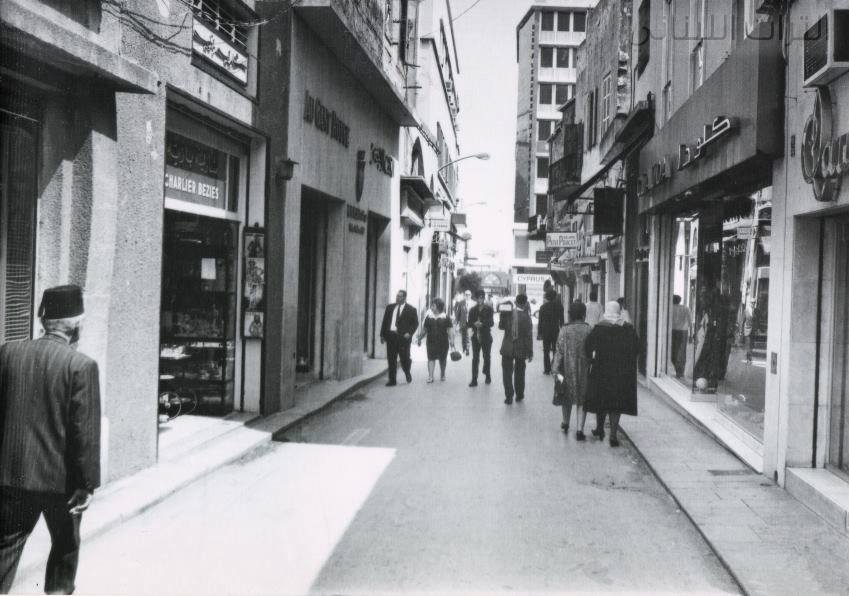

This area was primarily residential, the Yassine family lived in it, soon thereafter, shops started cropping up. Like all old markets, the shops invaded the streets. And in 1887, Beirut’s municipality had to intervene because it reached a point where if two people where coming towards each other, one of them would have to enter a shop to let the other one who’s coming towards him pass. That is how narrow the roads had become.

The municipality had begun expanding and organizing the street, paving the sidewalk, and if it didn’t do this, there would be no Souk el Tawileh.

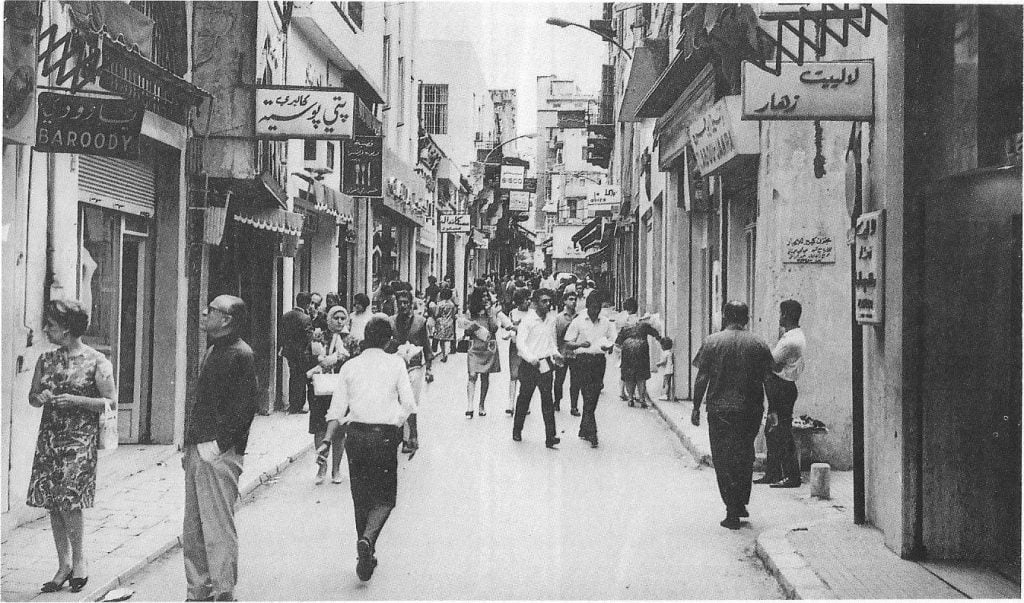

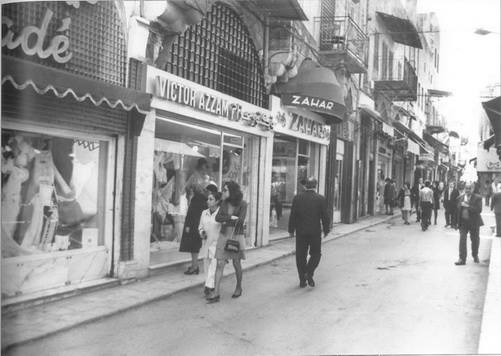

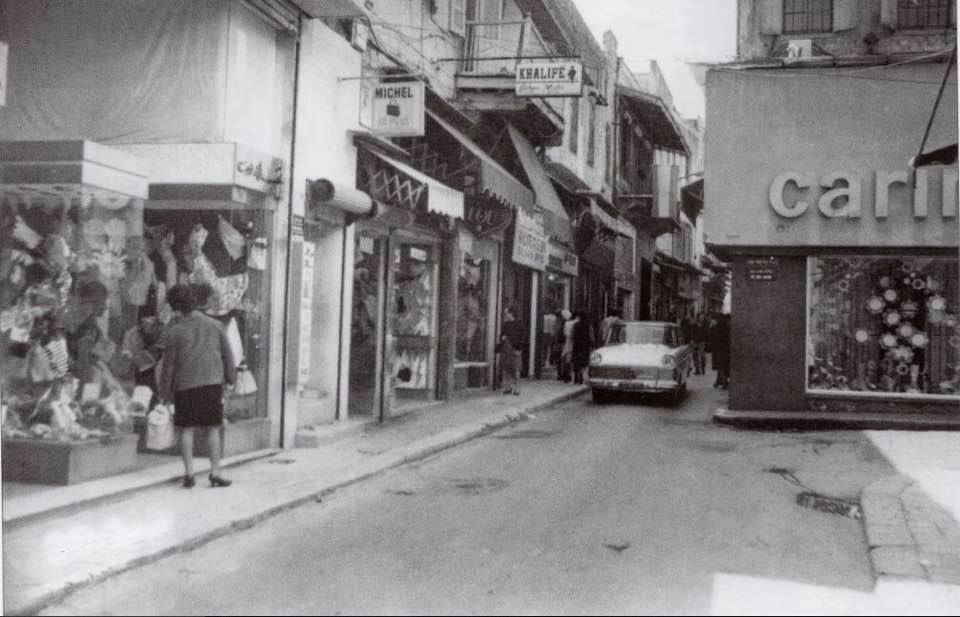

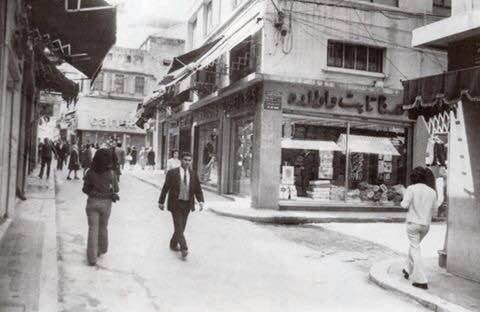

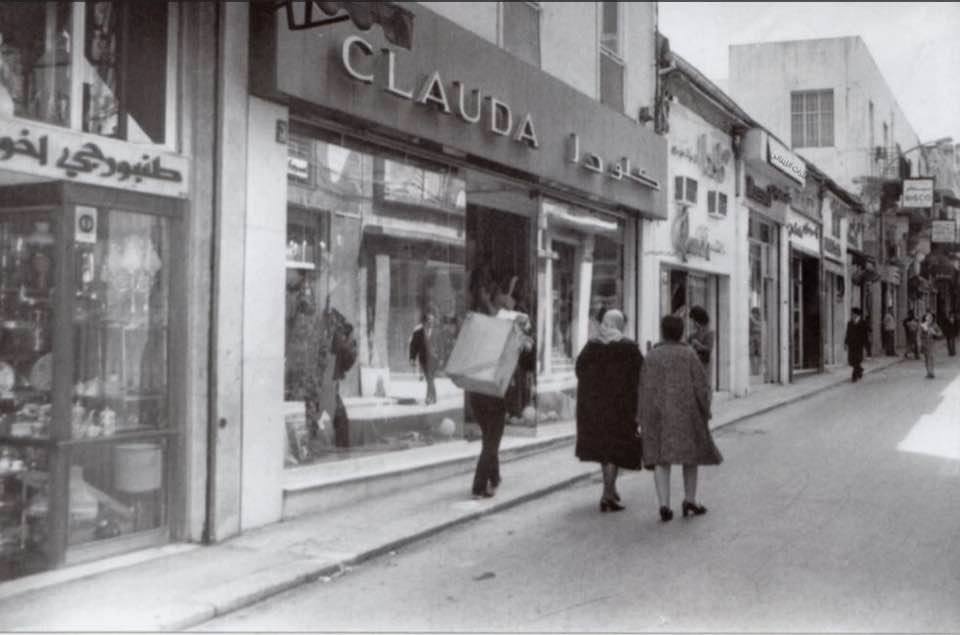

Now, on this street lived Al-Imam Al-Ouzai, and on it is was Zawiyat Ibn Iraq, this is from the last days of the Mamluks in 1517. But these are not the reasons for the popularity of the souk. During the 60s and 70s, it became renowned for being a destination for chicness, elegance, and fashion.

After being organized in 1887, it became famous for other things that came to Beirut at that time – most of the goods and products were from England, France, and Austria, with a wide variety of items being sold, not just clothes and fashion.

Before opening the jewelers market, Rouphael Homsi was a jeweler in Souk el Tawileh. And at that time, most of the craftsmen were working strictly on stamping and casting, meaning most shapes were the same. He changed things up and said I am ready to make whichever drawing or design you ask me for, and “upon examination, I’m either honoured or disgraced” and that was his ad.

Now, of the most famous shops in the market was a shop named Goldenberg. All of Goldenberg’s merchandise was from Austria, they used to import ready-to-wear clothes for women and kids, and they also imported Fez hats (tarboush). When the crisis between Turkey and Austria broke out in 1908, people gathered outside his shop with abadayet. They then began to remove their tarboush and throw them on the ground outside the shop. Some of them even came wearing Russian hats.

In 1893, Omar Al-Daouk opened the first watch and jewelry store. And speaking of watches, Fadlallah Al-Asmar used to sell grandfather clocks that were mounted on walls, and he used to sell a famous design called ‘Polaris Star’ and he had a phonograph that could transmit music up to half a kilometer away. Naoum Al-Asmar used to sell watches that needed winding every 8 days. Meanwhile, Ahmad Hasbini’s shop at the top of the Souk Al-Tawila used to sell dye created by Ahmed Fanoos from the Abu Al-Nasr market.

Now, if you’re walking along Souk al Tawileh towards the sea, suddenly you’ll find yourself passing between tables and chairs, you’re passing through Al-Ajami restaurant. Facing you is the L’Orient Le Jour building, on the corner to the right used to be the old offices of Annahar newspaper.

And we didn’t tell you after the hustle and bustle outside Goldenberg’s shop over them selling Austrian goods, they put up a sign announcing that they were selling only Italiano merchandise.

Join in for a new episode to know more and more what stories are hidden about Beirut, with a new story dropping every Tuesday and Thursday!

عندكن قصص أو أي تعليقات حابين تشاركونا اياها؟ بعتولنا بريد إلكتروني

collective-memory@beirut.com

To join the WhatsApp group that started it all and to tune in to more beautiful Beirut stories, click here

Join Group on WhatsApp

Sharing these stories would not have been possible without the work of following historians and researchers. If not for them and many others, Beirut’s heritage and history would have been lost. A special thanks goes out to:

Louis Cheikho – Taha Al Wali – Nina Jedejian – Hassan Hallak – Suheil Mneimneh – Abdul Lateef Fakhoury – Ziad Itani – Beirut Heritage Society – Ya Beyrouth Page